By Dr. Lisette Nieves

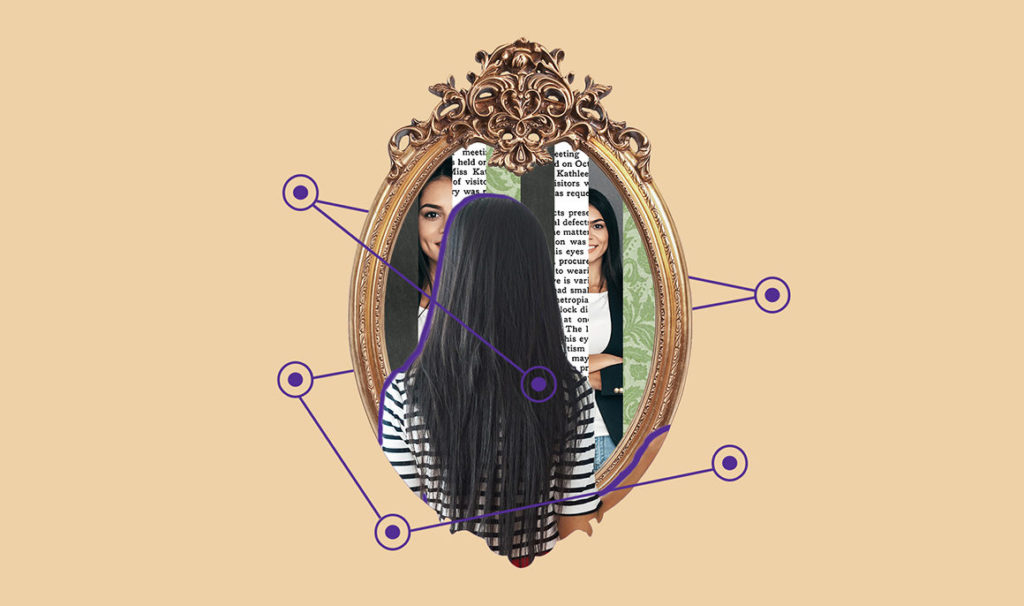

One of the required courses in the new NYU Steinhardt EdD program is Autoethnography. In creating and writing your ethnography, you focus on yourself. You answer fundamental questions about yourself. What message has your personal narrative conveyed to people – and you – up to now?

You might wonder why we include – indeed, require – such a course.

The most effective change-makers are those who are self-aware. Autoethnography compels you to identify and understand insights about yourself that are vital if you’re to make and manage real and lasting change as a leader. How can an educational doctoral program that develops leaders not include a course on who you, the leader, are? This course puts students’ personal makeup, intentions, and preexisting work at the center. It helps you start mapping out a leadership arc. We believe this to be an exercise in mindful leadership. Autoethnography is an invitation to become more self-aware, so that you may better understand your organization, your colleagues, and your goals.

In my own fortunate opportunities to lead, I have seen time and again, how my own learning – and letting others see me learn – does more to motivate and inspire my team than just about anything else I might do. As a manager or leader, making a point to show that you need and want to learn suggests that you are actively investing in your organization. Others pick up on this behavior and want to do it for themselves. The culture of educators getting more education and of leaders acquiring more tools to lead, is enviable and infectious.

Once upon a time, I was in the habit of asking my colleagues, “What do you do?” I thought that understanding their job responsibilities and their organizational structure was the best way to connect with the environment around me and understand how it worked. But that changed as I realized how much money was allocated for professional development, how many people used it, and that they came back renewed and changed. I stopped asking people what they did. Instead, when colleagues returned from professional development experiences, I started to ask them, “What did you learn?” I realized that the same should be true for me. Whenever I went for professional development, I made sure, when I returned, to talk to those around me about what I had learned and what was inspiring me. This nuanced but meaningful change in how we approached each other radically changed the outlook of my organization. “What did you learn?” tells people you’re the kind of person who is always digging deeper – that you have a distance to go before becoming the leader you hope to be, and that you’re willing to travel it.

Humility and self-awareness can be overlooked leadership assets. If you’re in a formal leadership position, you must – or should – constantly check yourself, your biases, and your limitations. You must continue to learn, perhaps foremost about yourself. You must be a strong listener, which also means listening to yourself. Without such self-awareness, it’s hard to understand and best help those in your organization.

Our underlying assumption at Steinhardt is that to truly lead change-making, participants need to know the who, what, and why of themselves to get effective buy-in from others. In short, to all those who imagine themselves as current or future leaders, one of the first questions we believe you need to ask is, “Who am I?” The better you can answer that question, the better leader you will be.